Sometime in 2017, when my friend Kay Suzuki first came up with the idea of starting a high quality reissue label, asking a bunch of us to act as curators, the first idea that came to my mind was a project dedicated to gwoka in general, and gwoka moderne in particular.

As a frequent visitor to the island for 25+ years (what with my dad working there as a professor), I gradually developed a strong love and affinity for the music coming out of Guadeloupe and the surrounding Caribbean islands.

Gwoka, bélè, rasin, rumba, beguine, kadans, kadans-lyspo, konpa, soca, son, zouk, reggae, jazz, blues, nyabinghi, funaná… The incredible array of music styles and genres which emerged out of the Caribbeans and the Americas as an indirect consequence of the slave trade has long flourished as one of the most fruitful cultural phenomena in history, defining much of our contemporary musical landscape.

An essential read on this topic is Paul Gilroy‘s highly influential essay ‘The Black Atlantic‘, a term which denotes a specifically modern cultural-political formation that was induced by the experience and inheritance of the African slave trade and the plantation system in the Americas, and which transcends both the nation state and ethnicity.

Also well recommended is the more recent ‘Ni noires ni blanches‘ by Bertrand Dicale, in which we learn about the constant thirst for creativity, as well as, for the most part, for cultural hybridity and creolisation from the artists and musicians occupying the space of this so called ‘black Atlantic’.

Some of these genres have benefited from the economic, political and symbolic power of the West, and others have emerged because they opposed that power. Some genres have been propagated by planetary stars and others by a dust of anonymous artists. Some have seen a fleeting fad and others have reigned for generations. Some have taken root in distant continents and others have seen only limited spread to nations of the South.

Gwoka, the music genre and art form which was born in direct reaction to the slave system in the French colonies, is deeply engrained in reality and the matrix of everything in Guadeloupe. Traditional singers are chroniclers of their time, memory smugglers who educate the audience by evoking values through their lyrics. Gwoka has always been protest music first and foremost.

*see bottom of the page for current examples of gwoka songs soundtracking the recent demonstrations in Pointe-à-Pitre.

I first encountered gwoka music, in its traditional form, during my first trip to the island in 1994. Every single Saturday between noon and three pm in Pointe-à-Pitre, in a street dubbed la piétonne, overlooked by the monument and spirit of Vélo, one of the most revered maître ka from the island, gathers an assortment of rotating musicians, percussionists, vocalists and dancers who, under the direction of Akiyo-ka, go through and improvise around a well known and well loved gwoka répertoire.

From toumblack to kaladja, the seven rhythms that define gwoka are played with pride and passion, week in week out. Absolutely unique, I never miss these gatherings (lewoz in Creole) when I’m in town and must have attended dozens of them, more often than not under the scorching midday sun with a few ti punch roasting my brains in unison with the mystical drums and entrancing maké soli. Unmissable.

In its traditional form, gwoka music is relatively well known, at least in France, and has been documented and compiled already, even if not as well as it should. Legendary maitres ka like the aforementioned Vélo, Ti Seles or Anzala, though not exactly household names outside of Guadeloupe, have long enjoyed some well deserved recognition, not only the island and within the diaspora, but also amongst true music connoisseurs. The art form gwoka (encompassing music, song, dance and cultural practices) itself has even recently been added by UNESCO on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (which didn’t seem to please everyone within the ka family, but that’s another story!).

What hadn’t been documented and put together though, is the emergence, from the 1970s onwards, initially under the impulsion of pioneers Gérard Lockel and Gui Konket, then via a few dozens of bands and artists, based both on the island or in the métropole, of new, creolised forms of gwoka, be they called moderne, modenn, évolutif or fusion. All of these artists were deeply rooted in gwoka history and well versed in the traditional répertoire, but were at the same time eager to experiment with hybridising or “modernising” the music, introducing new instruments like synths, drum machines, drum sets, guitars, saxophones etc.

Their styles vary widely but can broadly be grouped under the ‘gwoka moderne’ bracket (with the notable exception of the purist strand of Lockel‘s gwoka modenn style, which he theorised in a book and considered as an extension of gwoka traditionnel, “the only authentic Guadeloupean music”. That, also, is yet another story, which would deserve its own dedicated project and reissue – work in progress!).

(-_-) ♪ (-_-)

The discovery of Gaoulé Mizik‘s second album, the masterpiece Konbòch…, was a true revelation (the track ‘A Ka Titine‘ which features on the LP has long been a Beauty & the Beat staple, and will soon be reissued on BATB’s label), which kick started an ongoing quest for the most obscure and extraordinary holy grails in the gwoka moderne pantheon.

Through multiple visits and local contacts on the island, I quickly realised that most of this music was exceptional, and that is how the project for Time Capsule naturally came about. Having heard that Brandon Hocura of Séance Centre (who had himself compiled and reissued a superb retrospective on Robert Oumaou’s Gwakasonné) was working around a similar concept, we got in touch and quickly decided to join forces between the two labels and present some of our favourite cuts out of this scene which was never really one.

(-_-) ♪ (-_-)

I won’t lie, the process of finding and meeting all these artists and/or their descendants in order to license the tracks wasn’t always the smoothest, though every single one of these encounters will stay in my heart as the most rewarding part of the project.

I will forever cherish the times spent learning about gwoka history with Kalindi Ka‘s Marie-Line Dahomay, digging for treasures at Jocelyn Virapin‘s house, chatting with Selekta Ka‘s Jean Maccow in his terrace overlooking the rainforest, the many inspiring phone calls with Thibault “Freydy” Doressamy, as well as two surreal meetings in dodgy cafés in the Paris suburbs with Darius “Dao” Adelaide, during which he treated us first to an exhaustive oral history of gwoka, and the second time to a theatrical representation of both his classic tracks, ‘Chenn-la’ (listen below) and ‘Limyé Limé‘ (to be included as part of vol.2, if all goes to plan).

*see below

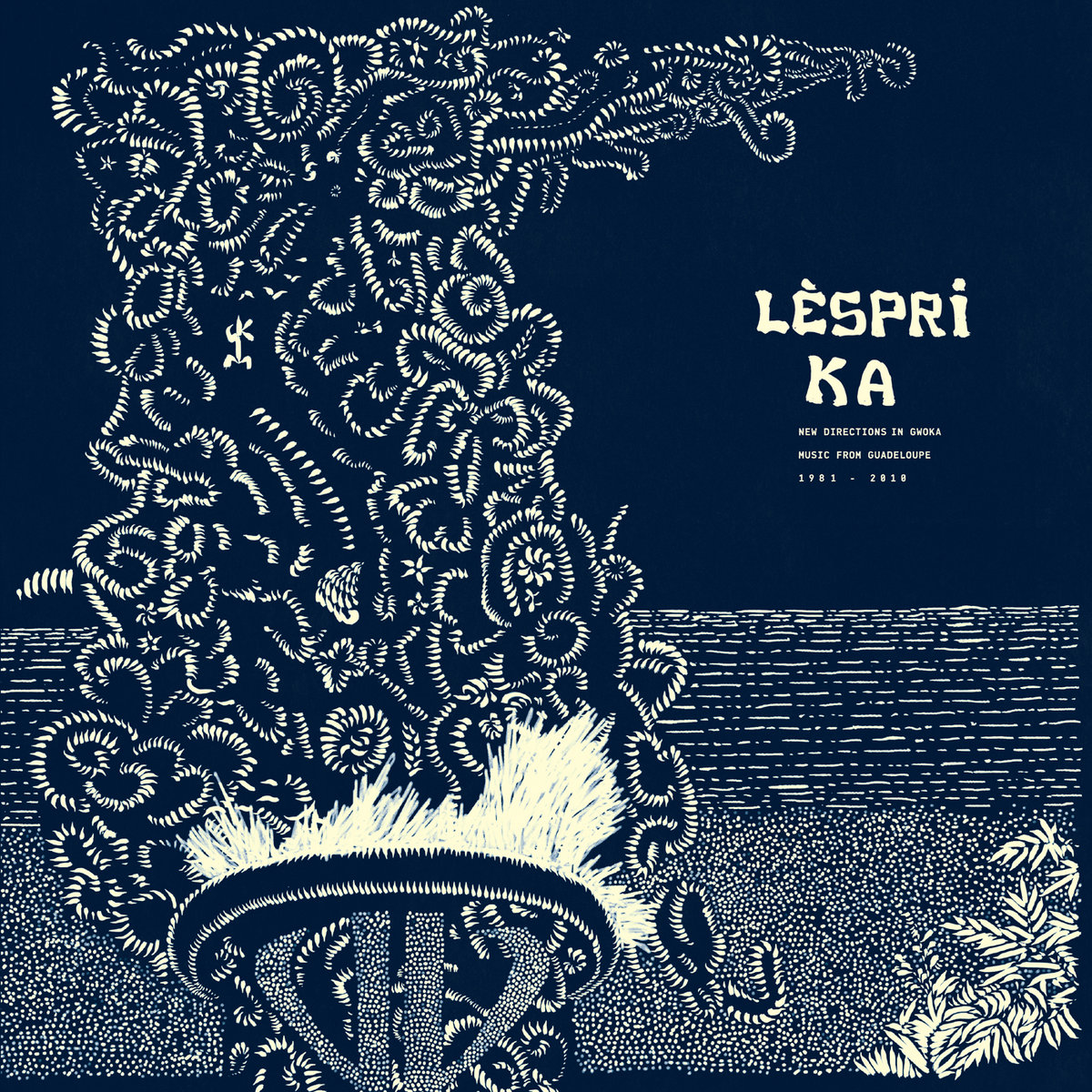

Link to the liner notes from Lèsprika

As a companion of the compilation, the great American journalist Andy Beta has published on Bandcamp a great article on gwoka, to which Marie-Line Dahomay and myself largely contributed (“New Directions in Gwoka“).

Last but not least, assuming you have now acquired and strong and refined taste for gwoka music, here’s a YT playlist I compiled of some of my favourite tracks, both of the traditional and modern form.

… and a recent mix I recorded for the great My Analog Journal YT channel, focusing on the modern side of gwoka:

Much love and gratitude to Marie-Line Dahomay, Jocelyn Virapin, Nico Skliris, Gustav Michaux-Vignes and Slim Bouzaoueche for your precious help towards this project.

*as mentioned above, gwoka music has been recently once again at the very heart of Guadeloupe’s daily life, soundtracking most of the demonstrations and social upheavals which have taken a grip on the island since the summer 2021 (the protests focused initially against the obligation vaccinale but quickly expanded and encompassed revendications against la vie chère, rising inequalities, lack of access to drinking water, education and health, but also the chlordécone scandal and more generally the post colonial attitude from the state towards its former colonies).

Here are two of the tracks often heard in the demonstrations:

- Ti Seles – La Mafia

- Dao – Limyè Limé

Bravo pour ses rééditions, le fils Anzala

Dominique mon ami est à rencontrer au Moule tout le monde le connaît

Salut,

Merci pour le feedback. Je serai en Guadeloupe dans quelques semaines et compte bien passer par Le Moule. Peut-être y rencontrerai-je Dominique!